Inside the nucleus of every cell lies a fascinating and dynamic structure known as the nucleolus. For decades, scientists understood it primarily as the site where ribosomes are produced, but recent research has revealed a much more complex and intriguing picture. The nucleolus is not just a simple organelle it is a collection of emergent microenvironments that form through liquid-like behaviors within the cell. These microenvironments of nucleoli organize and regulate many essential biological processes, including stress response, protein assembly, and genome stability. Understanding these emergent microenvironments gives us deeper insight into how cells maintain life and how disruptions can lead to diseases such as cancer and neurodegeneration.

The Structure and Function of the Nucleolus

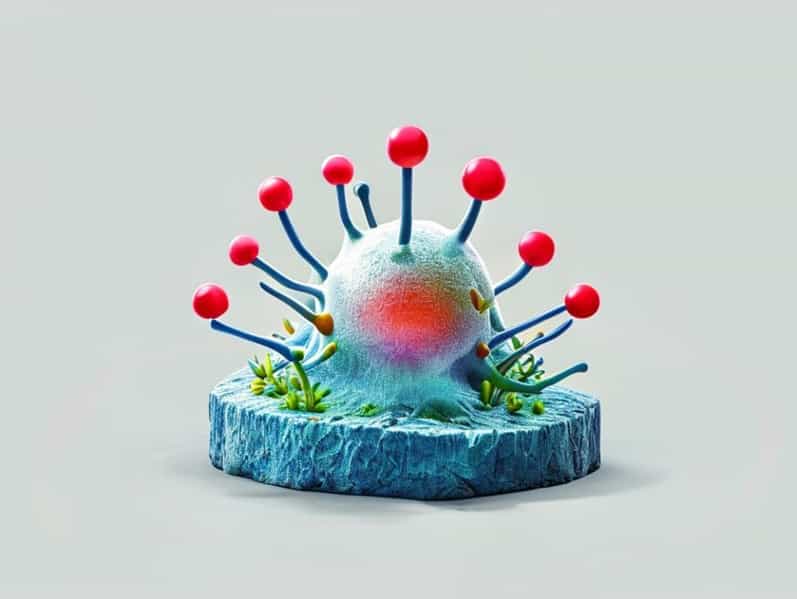

The nucleolus is the largest structure within the cell nucleus and lacks a surrounding membrane. Instead, it is a self-organizing body formed by the process of phase separation, similar to how oil droplets separate from water. Within this structure, there are distinct regions known as microenvironments or subcompartments that perform specific tasks. These include ribosomal RNA (rRNA) transcription, processing, and ribosome assembly.

Traditionally, the nucleolus is divided into three major regions

- Fibrillar centers (FC)The sites where rRNA genes are located and transcription begins.

- Dense fibrillar component (DFC)The area where early rRNA processing takes place.

- Granular component (GC)The region where late-stage ribosome assembly occurs before export to the cytoplasm.

Each of these compartments operates within a distinct biochemical environment, contributing to the overall function of the nucleolus. These separate but connected domains exemplify how emergent microenvironments can arise from the physical properties of biomolecules themselves.

Emergent Microenvironments A Dynamic Concept

The term emergent microenvironments refers to the idea that structures within the nucleolus form spontaneously from interactions between proteins and RNA molecules. These structures behave like droplets in a liquid, constantly forming, fusing, and separating based on changes in the cellular environment. Rather than being fixed, the organization of the nucleolus is fluid and adaptable.

Such behavior is an example of biomolecular condensation a process by which certain molecules separate from the surrounding nucleoplasm without the need for membranes. The result is the creation of specialized regions where reactions can occur more efficiently. These emergent microenvironments allow the nucleolus to carry out multiple tasks simultaneously, adjusting rapidly to the cell’s needs.

Physical Basis of Phase Separation

At the molecular level, phase separation occurs due to multivalent interactions among nucleolar proteins and RNA molecules. Many of these proteins contain low-complexity domains or intrinsically disordered regions that allow them to form flexible networks. When the concentration of these molecules reaches a certain threshold, they condense into droplets, forming the microenvironments of the nucleolus.

This dynamic organization provides a physical basis for cellular compartmentalization without membranes. It helps maintain spatial order inside the crowded nucleus while allowing fast molecular exchange and adaptation.

Functional Roles of Nucleolar Microenvironments

The emergent microenvironments of nucleoli are not static they perform diverse and essential biological functions. Beyond ribosome biogenesis, the nucleolus plays a central role in regulating cellular stress, controlling gene expression, and managing protein quality. These functions depend heavily on the internal compartmentalization within the nucleolus.

1. Ribosome Production

The primary function of the nucleolus is to produce ribosomes, the cellular machines responsible for protein synthesis. Within its microenvironments, rRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase I, processed, and combined with ribosomal proteins imported from the cytoplasm. The spatial separation of these steps ensures efficiency and coordination in ribosome assembly.

2. Stress Response and Cell Cycle Control

When a cell experiences stress such as DNA damage, heat shock, or nutrient deprivation the structure of the nucleolus changes dramatically. Its microenvironments reorganize to halt ribosome production and activate stress response pathways. This ability to dynamically adjust makes the nucleolus a key sensor of cellular health.

For instance, under stress, certain proteins are released from the nucleolus to regulate the p53 pathway, which controls cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. These responses demonstrate that the nucleolus is not merely a manufacturing site but also a central hub for signaling and adaptation.

3. Protein Quality Control

Emergent microenvironments within the nucleolus also act as storage or repair zones for misfolded or damaged proteins. During stress, misfolded proteins can be temporarily sequestered into nucleolar compartments to prevent them from interfering with normal cellular processes. Once the stress subsides, these proteins can be refolded or degraded appropriately. This mechanism underscores the nucleolus’s role as a quality control center within the nucleus.

Interactions with Other Nuclear Bodies

The nucleolus is not an isolated entity it interacts with other nuclear structures, including Cajal bodies and nuclear speckles. These interactions facilitate the transfer of RNA and proteins between different nuclear compartments. For example, small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), which are essential for rRNA modification, are processed in Cajal bodies before functioning within the nucleolus. Such coordination highlights how emergent microenvironments contribute to an interconnected network of nuclear processes.

The Role of Nucleolar Dynamics in Disease

Disruptions in nucleolar organization and its microenvironments have been linked to several diseases. Because the nucleolus is involved in cell growth and proliferation, changes in its structure often correlate with cancer. Rapidly dividing cells tend to have enlarged or irregular nucleoli, reflecting increased ribosome production and altered molecular organization.

In neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, abnormal phase behavior of nucleolar proteins can lead to the formation of aggregates or loss of function. This disruption affects protein quality control and stress response, contributing to cell death. Understanding how nucleolar microenvironments form and function is therefore crucial for identifying new therapeutic targets.

Examples of Nucleolar Dysregulation

- CancerOveractive ribosome production supports uncontrolled cell growth.

- Viral infectionSome viruses hijack nucleolar components to enhance their replication.

- NeurodegenerationMisfolding of nucleolar proteins disrupts normal condensation and function.

These examples illustrate how the emergent nature of nucleolar organization can be both a strength and a vulnerability. The same fluid dynamics that allow rapid adaptation can also lead to instability under pathological conditions.

Research and Technological Advances

Recent advances in imaging and molecular biology have allowed scientists to study the nucleolus at unprecedented detail. Techniques like super-resolution microscopy, live-cell imaging, and single-molecule tracking have revealed the dynamic motion of molecules within nucleolar compartments. Combined with biophysical models, these observations have strengthened the understanding that nucleolar organization is governed by the principles of soft matter physics.

Computational simulations have also been used to predict how proteins and RNA interact to form emergent microenvironments. These interdisciplinary approaches bridge biology, chemistry, and physics, providing a holistic picture of how life organizes itself at the molecular level.

Future Directions in Nucleolar Research

As research continues, scientists are exploring how manipulating nucleolar microenvironments might be used therapeutically. For instance, drugs that target phase separation or specific nucleolar proteins could potentially slow cancer cell growth or restore normal function in degenerative diseases. Understanding the emergent properties of these microenvironments could also help design synthetic biomolecular systems that mimic cellular organization.

Another exciting direction involves studying how environmental factors such as temperature, pH, and mechanical stress affect nucleolar dynamics. Since the nucleolus is highly sensitive to cellular conditions, it may serve as a real-time indicator of cell health, opening new possibilities for diagnostic tools.

The emergent microenvironments of nucleoli represent one of the most intriguing examples of self-organization in biology. Far from being a static structure, the nucleolus is a dynamic, multifaceted hub where biochemistry, physics, and molecular biology intersect. Through phase separation, the cell creates specialized compartments that perform essential functions without the need for membranes. Understanding these microenvironments not only deepens our knowledge of cellular organization but also provides insight into disease mechanisms and potential therapies. As research continues, the nucleolus stands as a remarkable model for how life creates order from molecular chaos.